It is “essential” that the genetic modification of human embryos is allowed, says a group of scientists, ethicists and policy experts.

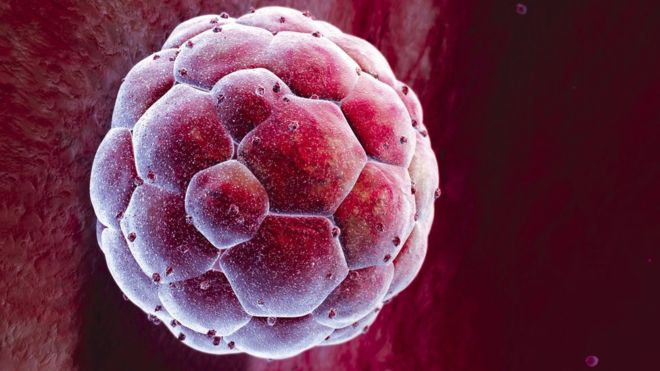

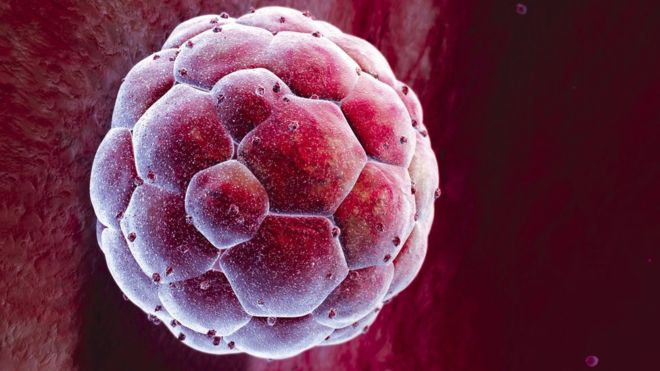

A Hinxton Group report says editing the genetic code of early stage embryos is of “tremendous value” to research.

It adds although GM babies should not be allowed to be born at the moment, it may be “morally acceptable” under some circumstances in the future.

The US refuses to fund research involving the gene editing of embryos.

The global Hinxton Group met in response to the phenomenal advances taking place in the field of genetics.

A range of novel techniques combine a “molecular sat-nav” that travels to a precise location in our DNA with a pair of “molecular scissors” that cut it.

It has transformed research in a wide range of fields, but the progress means genetically modified babies are ceasing to be a prospect and fast becoming a possibility.

Earlier this year, a team at Sun Yat-sen University, in China, showed that errors in the DNA that led to a blood disorder could be corrected in early stage embryos.

In the future, the technologies could be used to prevent children being born with cystic fibrosis or genes that increase the risk of cancer.

Embryo engineering dominates debate around these novel gene-editing tools.

But while disease-free children or “designer babies” may be on the horizon, the more immediate uses are far less controversial.

It could restore the reputation of the field of gene therapy in adults and children.

It was nearly a success in children with no immune system (known as bubble-boy syndrome). Symptoms improved, but the technique led to cancer in some cases.

These more accurate tools may be able to tweak our genetic code without the side-effects.

There have even been successful trials to give HIV patients immunity to the virus.

And because these changes would not be passed on to the next generation, they are far less controversial.

There have been calls for a moratorium on such research, which has left many asking where to draw the line – should any embryo research be banned, should it be allowed but only for research, or should GM babies be permitted?

A meeting of the influential Hinxton Group, in Manchester, acknowledged that the rate of progress meant there was a “pressure to make decisions” and argued embryo editing should be allowed.

In a statement, it said: “We believe that while this technology has tremendous value to basic research and enormous potential… it is not sufficiently developed to consider human genome editing for clinical reproductive purposes at this time.”

This is in stark contrast to the US National Institutes of Health, which has already refused to fund any gene editing of embryos.

Its director, Dr Francis Collins, who was also a key player in the Human Genome Project, said: “The concept of altering the human germline [inherited DNA] in embryos for clinical purposes has been debated over many years from many different perspectives, and has been viewed almost universally as a line that should not be crossed.”

However, the Hinxton Group’s full report acknowledges that “there may be morally acceptable uses of this technology in human reproduction, though further substantial discussion and debate will be required”.

But even one of the principal figures in the discovery and development of Crispr (one of the easiest methods of editing DNA) has doubts.

Prof Emmanuelle Charpentier told BBC News: “Personally, I don’t think it is acceptable to manipulate the human germline for the purpose of changing some genetic traits that will be transmitted over generations.

“I just have a problem right now with regard to the manipulation of the human germlines.”

Dr Peter Mills, from the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, added: “We have seen these uses coming over the horizon, but we need to decide whether we’re going to invite them in when they reach our doorstep.”

What is the Hinxton Group?

The Hinxton Group describes itself as an international consortium on stem cells, ethics and law, and brings together researchers, bioethicists and policy experts from around the world.

Named after the Cambridgeshire village in the UK where the group first met, its members aim to “explore the ethical and policy challenges of transnational scientific collaboration raised by variations in national regulations governing embryo research and stem cell science”.

Hinxton is also home to the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, where a third of the DNA sequencing work which led to the publication of the draft human genome was undertaken.